As a child, Christmas had a comforting predictability about it. Along with my grandma’s heavy-on-the-brandy Christmas cake, cut just in time for the Queen’s speech, there was always a foil-wrapped five pence that magically appeared in my pudding. But the real thrill every year was bound up with one stocking present I eagerly unwrapped before anything else – my Blue Peter annual. I still have my first – the ninth in the series (dating from 1972) – with John Noakes and Shep on the cover.

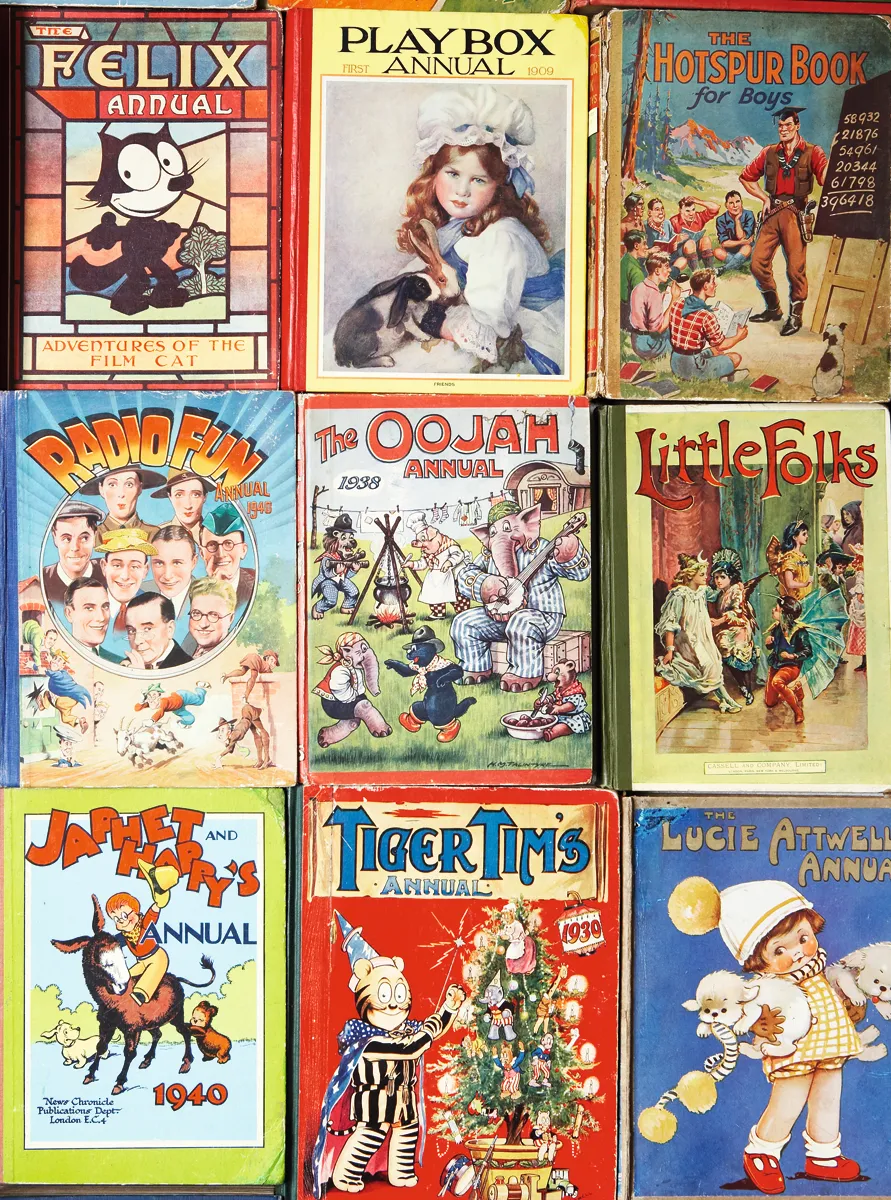

My love of these books, with their puzzles, pictures and ‘join in and make it’ mentality, is the continuation of a long-held family tradition. Back in the 1940s, my father was a devotee of Wizard Book for Boys (which ran from 1936-49) and, in the closing years of the Edwardian era, my grandma loved her Little Folks (1871-1933).

But in our electronic age, a battle for survival of comic-strip proportions has begun. Arrivistes such as the first official Moshi Monsters annual vie with Horrible Histories for pole position in Amazon’s 2012 popularity rankings. Meanwhile, the Blue Peter annual quietly bowed out of the race and disappeared this year after 46 issues and dwindling popularity (although not in my household, I must add). Against this backdrop, the trading of vintage annuals is buzzing. The adventures of yesteryear seem to have enduring appeal for the nostalgic who, like me, want to experience the thrill of annuals all over again.

When did annuals first originate?

The idea of an annual was a canny one if you were a publisher at the turn of the 19th century. Made up from a run of weekly or monthly magazines bound in plain hard covers, and with a few added extras in the form of pictorial title pages and advertisements, annuals offered printer-publishers a second chance to engage with their audience. The result was a standalone book that seemed fresh and perfectly timed for Christmas.

One of the earliest examples was The Youth’s Magazine; or, Evangelical Miscellany (first published by W Kent in 1804), a predictably pious tome, although ‘youths’ were treated to some tales of travel and adventure. Peter Parley’s Annual followed on, and thrilled readers for over half a century (1840-92), setting new quality standards with its steel engravings by noted artists and, from 1846, its printed colour illustrations.

The joy of some of these early annuals is that you often catch a glimpse of well-known authors and illustrators in another guise, sometimes very early on their career. The Little Folks annuals had stories by E Nesbit and illustrations by Arthur Rackham and Kate Greenaway, while Margaret Gatty, the founder of Aunt Judy’s Magazine (in 1866), regularly recruited famous contributors such as Hans Christian Andersen and Lewis Carroll. Indeed, the 1868 Aunt Judy’s annual contains a story by Carroll called Bruno’s Revenge, which later became the basis for the book that Carroll considered his masterpiece, Sylvie and Bruno.

Who were they aimed at?

Early on, annuals were aimed at those who had the benefit of an education – both adults and children. During the 19th century, annuals had overtly moral overtones and offered instruction for the young in the paths of truth and virtue. An 1878 copy of Little Folks’ contained this message for fibbers: ‘You have acquired a terrible fault – I might call it a disease; but remember, for your comfort, that is by no means incurable.’ Presumably, continued reading set culprits on the right path!

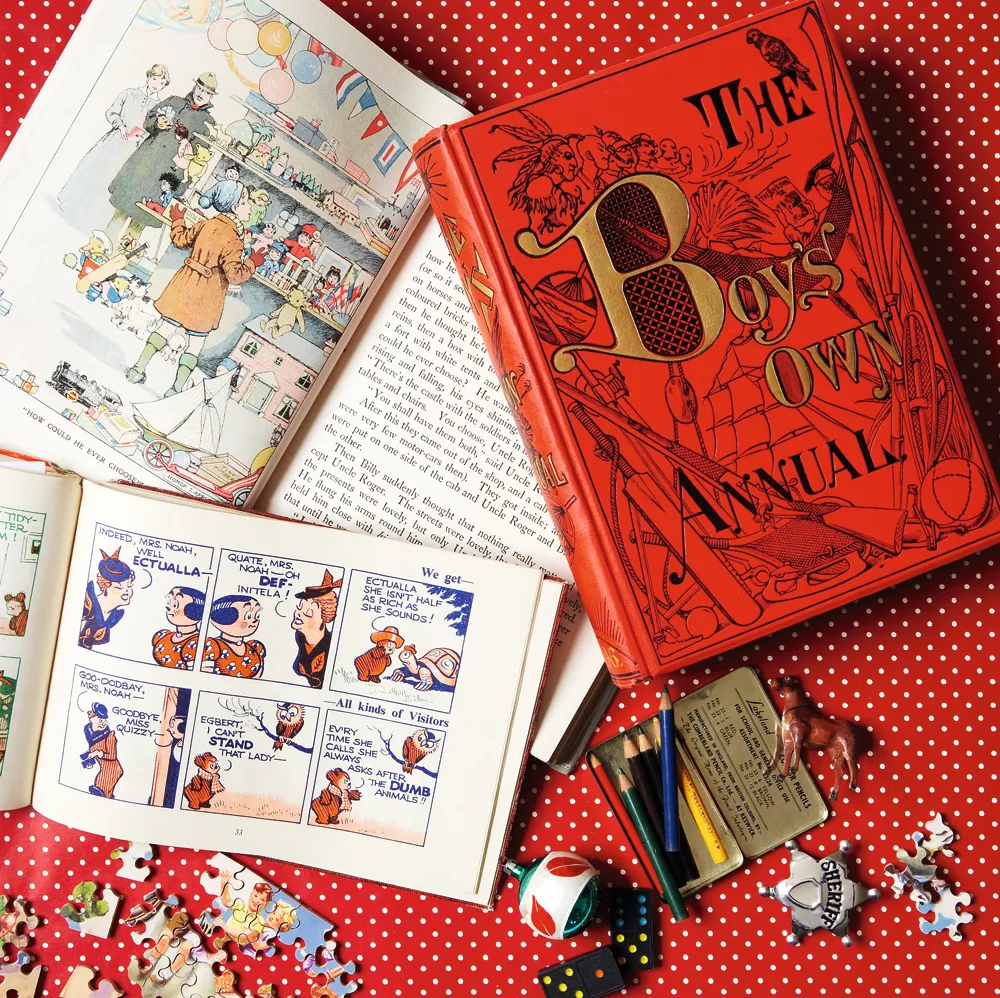

With the passing of time, dogmatic instruction was presented in a less obvious way and the children’s sections, which had been just part of the first annuals, took over. The Religious Tract Society, which published The Boy’s Own Annual (1879-1940) and The Girl’s Own Annual (1880-1948), guided its young readers through the bravery and honesty of its stories’ characters, while Dan Dare continued to stand for what is right well into the 1970s, with his appearances in the Eagle Annual (from 1952-74).

Comic and cartoon themes, which often followed newspaper strips, were first introduced via the Playbox Annual (from 1909) with readers’ favourite character Tiger Tim, who had his own annual from 1922. Children chuckled at the run of comic annuals that followed: Oojah (from 1923), Pip and Squeak (also from 1923), Beano (from 1940) and Dandy (from 1939). Interestingly, there were more boys’ annuals than girls’, although there were still a considerable number with dual appeal.

When was their heyday?

There have been several surges of interest in annuals over the decades. The first was at the end of the 19th century, when annuals proudly recorded Britain’s advances at home and achievements around the world. The 1870 Education Act gave a helping hand to literacy and this, coupled with cheaper paper and printing costs, helped to stimulate demand for annuals.

Interwar children who crushed into cinemas’ cheap seats on Saturdays were hooked on the new world of cartoons, which fuelled demand for annuals such as Felix the Cat and Mickey Mouse. Conveniently, there was more choice than they could ever have hoped for, thanks to a rivalry between the top publishers Amalgamated Press (Tiger Tim, Playbox and Film Fun) and DC Thompson (The Beano, Dandy, Rover and Hotspur) – both companies were keen to dominate the market. But perhaps the greatest peak in terms of sales volumes came when television took hold and youngsters, like me, wanted to get up close and personal with the stars of their favourite TV programme, be it Captain Scarlet or Sooty.

How much do they cost?

The joy of annuals is that there really is something for every budget. Part with £5 and you’ll take home a later issue of Radio Fun or Playbox. For a little more, the world of vintage Bunty (£10-£20), Champion (£20), Crackers (£35) or a 1970s Rupert (£20) could be yours. A real rarity, such as the brown-faced Rupert of 1973 (see box), will go for much more. The first or very early books in the run of most titles command a premium – a 1938 copy of the Mickey Mouse Annual (the eighth) sells for around £165 but a recent eBay auction ended on £700 for a nice copy of the 1932 edition (the second). Remember, whatever you opt for, it will be a first edition: if they sold out, that was it. The only exceptions are later facsimile editions of true rarities, which carry the relevant disclaimers.

As you would expect, clipped corners, missing plates and worn bindings dent an annual’s value quite significantly. Just occasionally, you may find a rare edition with sparkling facsimile coloured plates, slotted in for effect to replace torn out illustrated pages, so do keep an eye out. Some annuals (exactly how many remains a mystery) were issued with dust-wrappers and, although they don’t add quite the same premium as they do on books, they are nice to see as they were often beautifully pictorial.

It’s at this point I must add that my unscribbled-on and generally immaculate copy of the Blue Peter annual from 1972 is actually worth no more than a fiver. So, ‘Dear Santa, please could I have that brown-faced Rupert this year?’

Photographs: Rachel Whiting. Styling: Kiera Buckley-Jones