Some artists’ studios are neater than a new pin, but Peter Beard’s Warwickshire workshop is a jumble of objects and tools. A throwing wheel lurks beneath spatters of clay, plastic tubs of soupy glaze are gathered together against one wall, and ceramic vessels in various stages of completion sit higgledy-piggledy wherever there’s space. ‘I sometimes think about having a bigger workshop, but I know I’d end up filling that too,’ says Peter.

Gritty though his workshop, a converted barn at the end of the garden of the farm cottage he shares with wife Hilary, undoubtedly is, from it Peter produces exquisite, intricately glazed stoneware, priced at £120 to £1,500. ‘Everything is a one-off piece of work. I’m not interested in fashion – I want to make beautiful things for people to enjoy all their lives,’ he says of the hand-thrown and hand-built wares that he has been making since the 1970s.

Peter, 57, moved from Kent to rural Warwickshire 12 years ago, but his passion for potting goes back to childhood when, as a teenager, a local potter gave him a Saturday job and encouraged him to make things. Though it seemed obvious to almost everyone, including Peter, that he was destined to be a potter, his parents wanted him to get a ‘proper job’. As a compromise, he studied Industrial and Furniture Design at Ravensbourne College of Art in London. The pottery bug wouldn’t go away though. ‘I ended up spending all my time, from dawn to dusk, in the pottery department. That said, I did learn about lots of other materials such as wood and plastics too, which has proved invaluable.’

After his degree, he followed his heart and moved to Scotland to help establish a pottery making domestic wares. He stayed a year then returned south. ‘It was a good experience because I realised it wasn’t for me – I wanted to make things of a decorative nature,’ recalls Peter.

He opened his first solo studio in Kent in 1975. Now his work is in over 16 public and private collections, including Norwich Museum, Stoke on Trent City Museum and ceramics centres in Germany, Switzerland, Japan and Korea. He has won several awards, including the peer-judged Pot d’Or at Keramisto, Holland, in 2000. And, in 2004, a research grant from the Arts Council led him to start working with bronze and stone, too.

Sharp focus

Peter’s working day is intense, starting at 6am, when he rises to check the kiln. Then he begins a patchwork of tasks, such as drawing, throwing, glazing, and mounting pieces on hand-cut slate, that continues through to the evening. ‘It’s not a production line – I make the things I like and try to sell them. I throw a maximum of 10 items at a time, and something could wait a few months until I feel ready to decorate it. I tend to make pieces in series, but I’ll stop doing a design if I’m not getting any more stimulation from it.’

His simple, organic shapes are very rarely a direct representation of anything specific, rather a distillation of various observations ‘that get tumbled around inside my head’. He likes Neolithic axes, shells, sails and rippled water, for example, and began making his slab-built discs after a trip to China in 1978, where he was inspired by jade rings.

‘I never go anywhere without a sketchbook – if I see a nice stone or a piece of wood I sketch it. I do a lot of drawing before I make something,’ says Peter. A travelling scholarship to Egypt in 1990 was a landmark experience. ‘I’ve always been interested in ancient Egypt and there are resonances in my work of the things I saw there, such as the wind-driven sand in the desert and the traditional falucca sailing boats.’

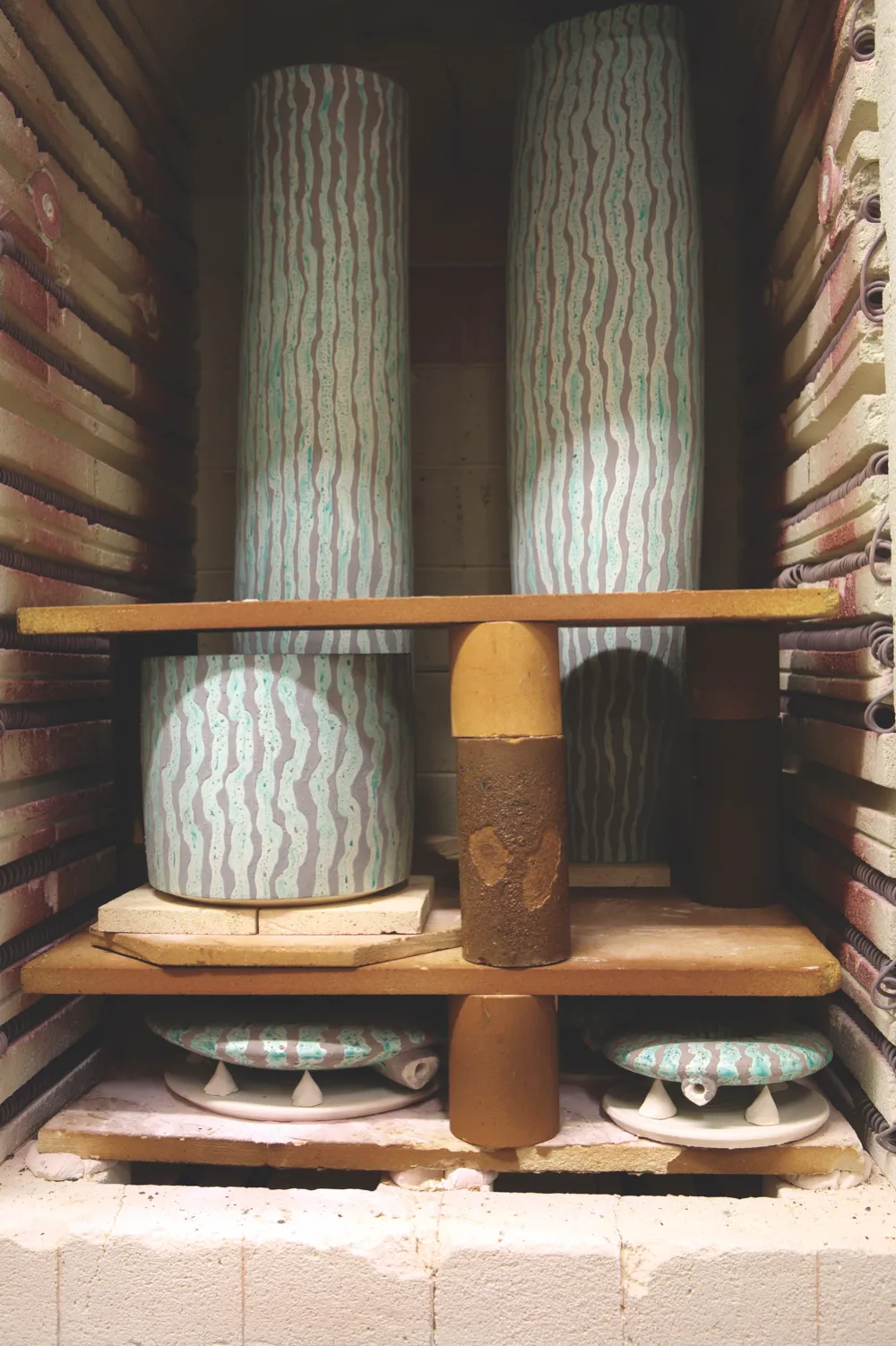

While shape is a key element of his work, Peter’s decorative style makes it truly distinctive. He is constantly experimenting with glazes and, even after a lifetime’s experience, every kiln-load of work includes a glaze test to assess a new colour or the viscosity of glaze mix. ‘I don’t find it difficult to get ideas – it’s the execution and the decoration that takes the time,’ he explains.

His favoured oxide glaze colours are blues and greys, burnt oranges, lime and bright greens and pinks – all eye-catching in their own right, but made even more arresting when combined with Peter’s method of using wax relief to create texture. Masking glazes and areas with wax allows layers of pattern to build up, making the surface almost three dimensional and very tactile – ‘wanting to pick it up is part of the enjoyment’ – and some pots feel rougher than others. The interiors of the vessels are glazed too. ‘The inside of a pot is very different to the outside – it taps into another set of emotions,’ he says.

Double glazing

When he’s applying glaze, Peter works intensely, hermit-like, as the process requires maximum concentration. Before being decorated, the biscuit-fired vessels and objects are dipped into a bucket of thick, matt base glaze. For the subsequent wax relief technique to work the coverage has to be perfectly even, so he spends time sponging and scraping away excess glaze.

Once the base glaze is smooth and dry – around 20 minutes or so – the vessel is ready to be decorated with between two and four oxide glazes. First, to compose the pattern, Peter draws freehand lines using pink food colouring applied with a delicate brush. Next, he paints liquid wax following the lines to mask certain areas. Finally he paints on the coloured glaze, again following the lines, with the wax acting as a resist. He does this with great precision, despite the lines’ wobbly appearance. ‘I like there to be movement in a line,’ he says.

It takes him several days to decorate enough work to pack a kiln, and as each vessel is finished and ready to fire, Peter gently places it onto the firing shelves, checking that there is no unwanted chip or glitch on the glaze. Seconds are never available because he simply discards work that he doesn’t regard as perfect. ‘Because I put so much of me into my work, it has to be good. After all, that’s what people are paying for.’

COLLECTING PETER BEARD CERAMICS

Roadshow expert Jon Baddeley has been a fan for two years. Peter Beard’s ceramics first caught Jon’s eye at a London ceramics fair. ‘I’ve worked in collectables all my life,’ says the Bonhams director, ‘and contemporary ceramics are a real bargain compared to modern art and sculpture.’

‘Peter has a distinctive, daring style. I love his glazes – his use of colour is very unusual, and I particularly like his shell shapes. My wife and I now own four pieces of his work, which look beautiful among our collection of antique ceramics such as Royal Lancastrian and high-fired Ruskin wares. It’s hard to say how good an investment it is but, if you like someone’s work, you should form a collection. Buy larger pieces if you can afford to – the more you spend, the more important the piece is, because it will have been more difficult to make.’

Peter’s work is stocked at Aldeburgh Contemporary Arts, Suffolk, 01728 454212; The Old Courthouse Gallery, Ambleside, Cumbria, 015394 32022, and The Stour Gallery, Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire, 01608 664411

FEATURE: Caroline Wheater

PHOTOGRAPHS: Lydia Evans