'Photos never do justice to the beauty of Bitossi,’ explains collector Laura Cowling. ‘It’s incredibly tactile pottery. All Bitossi pieces are hand-thrown and hand-painted. I love the individual grooves pressed into the surface of the clay, the slight grittiness in the glaze, the way the dribbles of colour merge together. Each piece is unique.’

Bitossi Ceramiche is a family-run firm, which traces its involvement in the creation of ceramics over many generations. Before the Second World War, the company’s output was mainly utilitarian – cookware, floor and roof tiles. Many of their competitors’ factories were destroyed during the invasion of Italy, but the Bitossi works survived, mostly intact, which enabled the family to expand their business activities after the war. As well as supplying glazes and raw materials to other Italian producers, Bitossi’s own art pottery business grew rapidly.

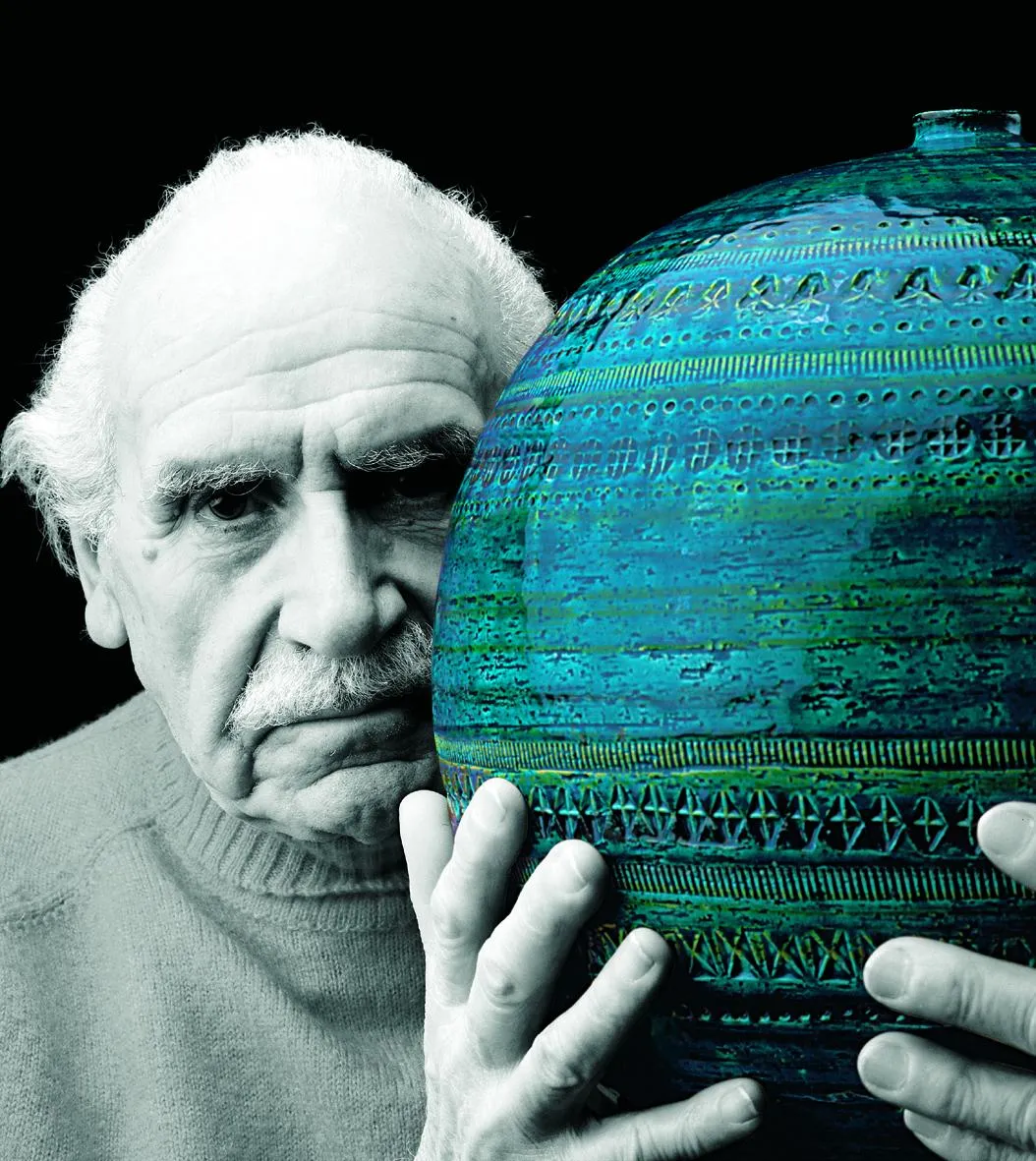

Undoubtedly, the appointment of designer Aldo Londi – responsible for some of the company’s boldest, most stylish and innovative output – explains the success of the pottery from the 1950s onwards.

Born in 1911, Londi became an apprentice at a ceramics manufacturer aged 11 and joined Bitossi in 1946 where he was soon appointed artistic director. Many items from the Rimini Blu range, one of Londi’s most famous creations, have been in more or less continuous production since their introduction in 1959.

Mark Hill has carried out extensive research into the history of Bitossi and, in his book Alla Moda, he explains how to spot older Rimini Blu examples – items made in the 1960s and 70s tend to have greater depth and range in their colouring, and the glaze is heavier and more viscous. Prices range from £30 for small mid-century pieces to hundreds for hard-to-find pristine original models.

Although Aldo Londi is Bitossi’s best known and most influential ‘name’, for decades the company has collaborated with other designers, architects and artists, seeking to be at the forefront of exciting ceramic design. A glimpse at the company’s private archive reveals its eclectic output: bulbous vases swimming with pastel-coloured fish; lustre-glazed trinket dishes; delicate elliptical bowls; and gravity-defying vases. Since the early 2000s, the company has reissued some of the iconic mid-century pieces in its archive, such as Ettore Sottsass’s oversized monochrome chalices and bold table centrepieces.

Bitossi’s striking animal designs, especially the earlier pieces, are highly sought after. Collectors love the playful, naïve quality of the menagerie, which includes cats, dachshunds, hedgehogs, horses, bulls, lions, elephants, owls, doves, ducks, hippos and turtles. The variety of Bitossi creatures is something that appeals to collectors, who are always thrilled to discover one of the more unusual models, and willing to pay for their rarity. Unsurprisingly, midcentury mint condition, signed animals in the more unusual colours (red, yellow and orange) fetch the highest prices.

Over the years, Bitossi used a range of different markings, which can be confusing to the novice collector. The earliest examples, produced until the early 1950s, are identified on the base with a letter B, with or without a full stop and sometimes underlined. From the 1950s to 70s, the company’s products were marked in several ways, usually incorporating a handwritten design number and ‘Made in Italy’ or just ‘Italy’. Contemporary pieces are impressed with the Bitossi name and family crest.

However, some authentic Bitossi pieces aren’t marked at all. Bitossi produced thousands of items for export, often to the United States. Sometimes they reproduced existing Bitossi designs, and sometimes they made special new commissions. Occasionally, the sticker of the secondary retailer survives on the base – collectors look for the names of American importers Rosenthal Netter and Raymor. But it’s not unusual for the sticker to have been lost or deliberately removed, making attribution more challenging.

Like other successful pottery makers, Bitossi’s work has been widely copied, but sometimes pieces that are confused with Bitossi aren’t deliberate fakes. As Bitossi supplied the raw materials required for the manufacture of ceramics, items made by other Italian producers can appear superficially similar, although they tend to lack the characteristic Bitossi panache, and are generally of lower quality.

Walter Del Pellegrino, who runs an online Italian ceramics forum, is inundated with requests to help identify Bitossi. He estimates that roughly 65 per cent of so-called Bitossi pieces sold in online auctions are wrongly attributed.

Despite some of the mysteries involved with identifying Bitossi, collector Laura Cowling neatly sums up its enduring appeal: ‘Ten years ago, I was really into mid-century design, but we moved to the countryside and gradually I’ve bought older furniture and got a lot chintzier. Because it’s handcrafted, and echoes some of the shapes and colours of traditional Italian maiolica, Bitossi fits well with both looks. I still use my Bitossi – it doesn’t just sit on a shelf gathering dust. Arranging dahlias in my favourite Chartreuse yellow ‘Spagnolo’ jugs always makes me smile!’