With the Chinese antiques market thoroughly picked over in the last few years, collectors with deep pockets have instead been turning their attention to the field of Buddhist antiques to fuel their passions. Of particular interest are the mid-to-high level gilt bronzes and Thangka scroll paintings of the east Asian and Himalayan regions (such as the one Gordon Watson mused on in his column for Homes & Antiques' June issue), especially those with Chinese connections.

To those who know the field, the collecting shift is unsurprising. Despite the recent political opposition to Buddhism by the Chinese authorities, the art history of 17th–19th century Asia is largely dominated by the workshops and travelling artisans of Buddhist Imperial China. For the Chinese individuals who dig deep to repatriate their ancestors' greatest achievements, it's hard to overlook this fact for long.

The first signs of a price explosion occurred at the 2014 Asia Week in New York. Prices are always a little inflated during these events, but a good number of items astounded even the auctioneers as they soared far in excess of their estimates. One New York collector I know put it into perspective. He reminded me that with most of the very top level items already tucked away in museum collections, this latest wave of private collectors is having to fight over relatively limited offerings. Indeed in November 2014 a 15th-century embroidered thangka with direct links to the Imperial Court, set a new world record of $45m (around £29m) at Christie's making it the most expensive Chinese work ever to sell at auction.

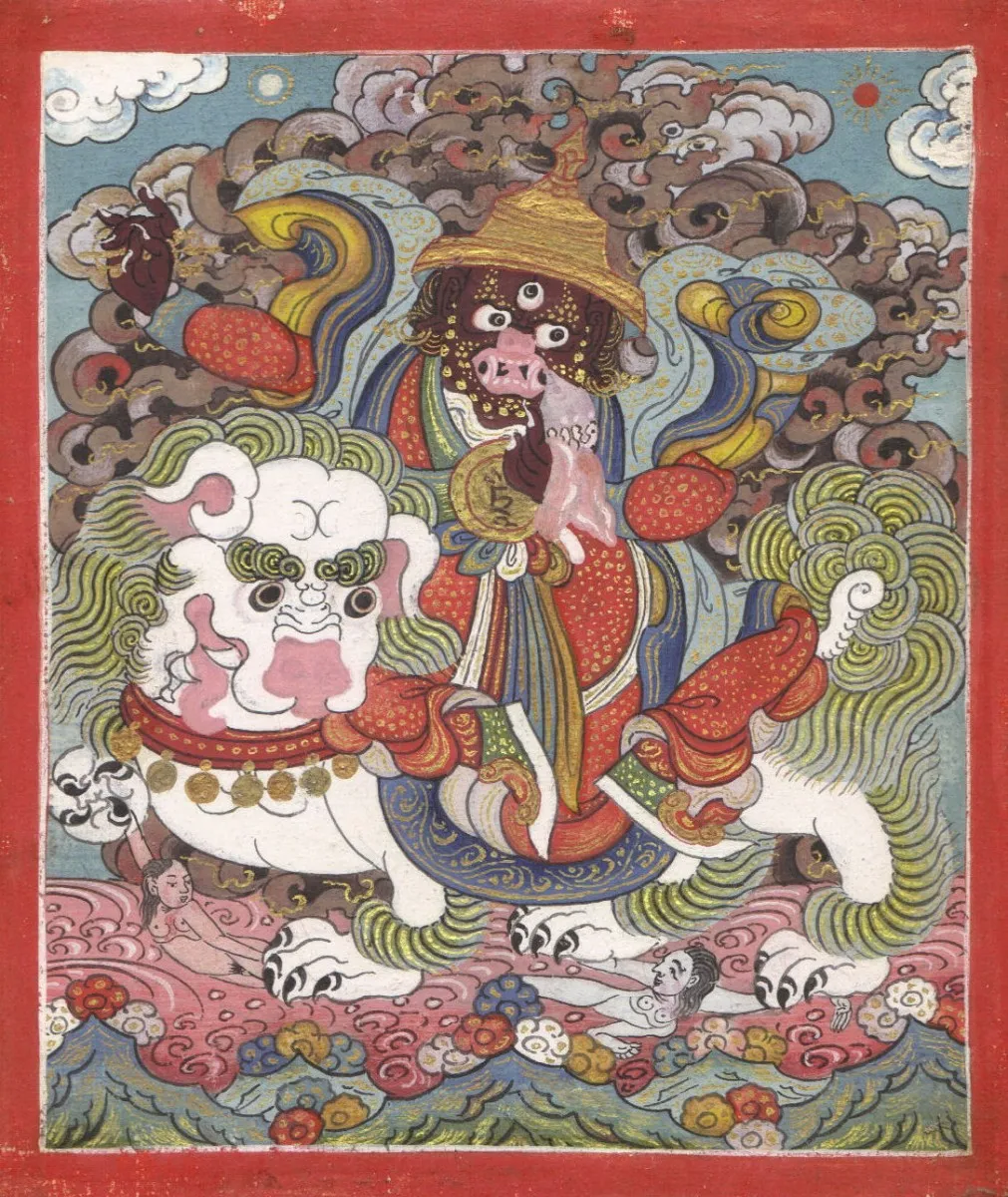

The surge has not gone unnoticed. Flick through any current antiques trade magazine and it will be littered with Buddhist statues and paintings offered by auction houses up and down the country. I feel a twinge of pity for the novice buyer as trawling through a recent list of upcoming auctions I spotted a good number of lots that had errors either in date, country of origin or attribution of the deity. It's a field that demands diligent study for auctioneers, not least because of the complexity of the vast pantheon of Buddhist gods.

Unlike our western tradition that has always promoted individual expression and style, Buddhist art is primarily a teaching tool that promotes exact repetition. Except in a few rare cases (such as depictions of living teachers), unsigned repetitions have always been expected. Not that differences between eras and countries can't be discerned but they are slower to appear and less geographically confined.

Spotting these subtleties can be a very refined art. For example, while Chinese painters typically preferred a more vibrant colour range (even psychedelic at times), it's not a rule. Artisans constantly travelled across borders to work and teach so cross-pollination was rife. To appraise a piece you have to look for a host of other subtle signs such as Chinese facial structures and more craggy background scenery (compared to the softer hills found in Tibetan and Mongolian paintings). Add to all this subtlety the mass of relatively modern (but now worn) tourist copies and outright fakes that have emerged since the hippie surge of the 1960s and you can see why we should all be treading carefully.

I’ve had a vested interest in the Buddhist art of the Himalayan region for over a decade now so this recent surge is exciting. Having lived for several years in Mongolia I had the unique privilege of handling some amazing items as well as interviewing the modern masters who were still producing them. At heart these objects are devotional and were originally intended for teaching. Despite years of rigorous training, most artworks remain unsigned to ensure the artisan does not pick up bad karma through false pride. It is a testament to their craftsmanship that many dedicate years to a single piece repeating prayers and meditating upon each brushstroke or mould mark.