Carrying snuff was once as commonplace as carrying a phone. But as author Kenneth Blakemore remarks in his history of snuff boxes, ‘The art of snuffing is all but unknown to us today: all that remains of this once fashionable habit are the miniature boxes, intricately designed and coloured, which were once coveted by people in all walks of life – from royalty to peasants – throughout the world.’

Tobacco was first imported to Europe from the Americas in the 1500s. Smoked or snorted, it was touted as a medicinal cure for everything from headaches to the plague. By the 1600s ‘snuffing’ – inhaling finely ground tobacco through the nose – had become a widespread social habit.

But it was not universally celebrated. In 1624 Pope Urban VIII issued a decree excommunicating anyone using snuff on church property. In the 1640s, Tsar Michael 1 of Russia banned the import of tobacco, ordering that snuff-takers should have their noses cut off.

Despite attempts at prohibition, in the 18th and early 19th centuries both noblemen and women took to snuffing with gusto. Netflix’s flamboyant Regency romp Bridgerton depicts Queen Charlotte snorting snuff. It is one of the show’s more historically accurate elements – the real Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, was a snuff devotee, lampooned as ‘Snuffy Charlotte’.

- You might also like everything we know about the Bridgerton spin-off

Among the fashionable elite, a complex set of steps accompanied the practice of taking snuff: tapping the box three times to settle the tobacco, offering snuff to the assembled company, taking a pinch from a tiny spoon or from the back of the hand and delicately dabbing the dribbling nose with a coloured handkerchief (coloured so as to hide the ugly tobacco stains).

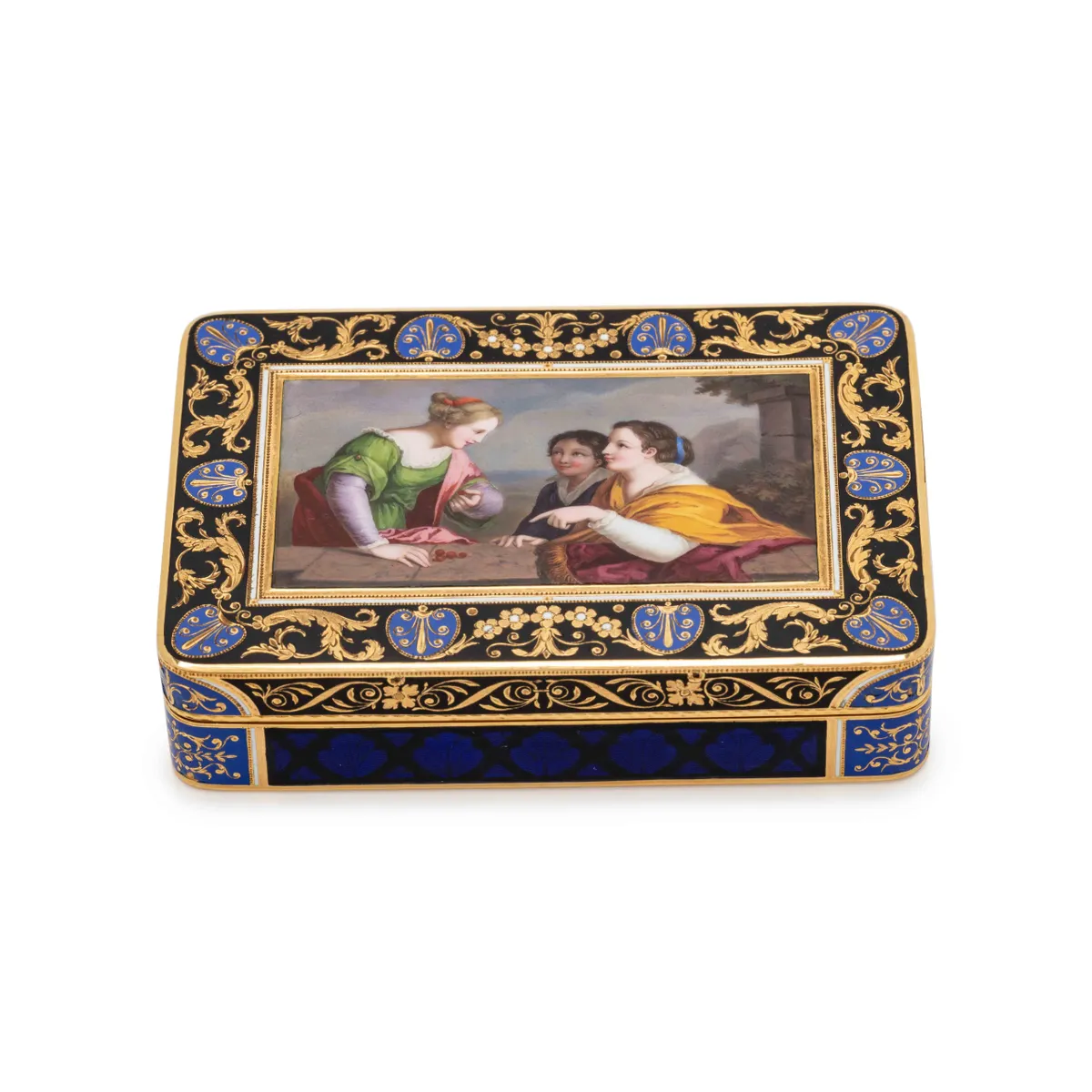

The ease with which this ritual was accomplished signalled the refinement of the snuff-taker. Even more important was the box the snuffer flourished – nothing said ‘I’m filthy rich’ quite like producing a gold box encrusted with diamonds from your pocket.

For the nobility, different outfits, occasions, or seasons all demanded different boxes. In his book, Kenneth Blakemore describes the snuff box collection of Madame de Pompadour – chief mistress of King Louis XV of France, who owned hundreds of examples in ivory, enamel, tortoiseshell, and gold-mounted malachite, and boxes lavished with dragons and butterflies.

As with other imported luxuries, like sugar and tea, the use of tobacco filtered down to the rest of society. Snuff boxes were made in papier-mâché, horn, ceramic and a huge range of other more affordable materials. Even a farm labourer might carry a pinch of snuff in a small wooden box in his waistcoat.

Today these humble wooden boxes can be sought after by collectors, says Sally Honey, a dealer who specialises in treen at Opus Antiques: ‘Some wooden boxes were professionally made, but others you imagine being carved by candlelight in a little cottage. There’s an incredible range of sizes, styles and novelties made in wood. We see shoes most often, which symbolised luck, and much more rarely objects like clocks, chests of drawers, hats and purses. Bellows might be given as love tokens – to warm the heart. Animals like horses, monkeys, lions, frogs and fish are not so easy to come by, and so make a lot more money. Comical little men carved from coquilla nuts are also very desirable. They have so much personality.’

Given the vast range of styles and materials, how can we identify boxes specifically designed for storing snuff? ‘Unlike other kinds of box, such as bonbonnieres, the form of snuff boxes has a very specific requirement,’ explains Nick Coombs, a specialist valuer at US auctioneer Hindman.

‘They have to protect the snuff and stop it from drying out. Generally, they have a high rim on the interior and close very tightly, often with a strong hinge, so they are as airtight as possible. There’s a range of sizes – some hold a small amount of snuff for a single day’s personal use, others are designed to sit on a table with enough snuff to share socially.’

In October 2022, Hindman sold a single owner collection of rare and valuable boxes, including snuff boxes, which wouldn’t have looked out of place at a royal palace like Versailles.

‘High quality boxes like these weren’t just designed for communicating wealth and status. They also demonstrated the owner’s exceptional taste and appreciation of fine craftsmanship. One of the boxes sold in October bore the coat of arms of an eighteenth-century French aristocrat, the Duc de Choiseul, who was well-known for commissioning exquisite snuff boxes. It’s a multipurpose box modelled in gold as a classical female bust. The body is hollow so that it can be used for scent. The base flips open to reveal space for a small amount of snuff, and the bottom can be used as a seal.’

‘Boxes like this are one-of-a-kind and incredibly rare,’ continues Nick. ‘They’ve survived 250 years - wars, revolutions, economic troubles – and are in remarkable condition. It’s possible they were luxurious gifts, intended to be displayed and admired, and never really used.’

Nowadays, snuff-taking strikes many people as a horrible habit. It’s strange to think that such charming objects were ever associated with all that snorting, sneezing, dabbing and dribbling. But with boxes to suit all tastes, and budgets, snuff box collecting might turn out to be just as addictive as taking snuff.

How much do snuff boxes cost?

A simple beech snuff box could be found for as little as £20. At the other end of the scale, in July 2011 Bonhams in London sold a Meissen gold-mounted snuff box made for Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, for a record-breaking £860,000.

Nicky Gould, a dealer who sells snuff boxes, explains what makes some boxes more valuable: ‘When stock markets around the world are struggling, investors look for alternatives. At the top end, the very luxurious boxes with intrinsic value, for example in solid gold, are really increasing in price. The value of a midrange snuff box is usually determined by how interesting or unusual it is – boxes with lots of character tend to make more, especially the earlier boxes from the eighteenth century.’