In January a friend sent me an excited text having just discovered Nottingham’s ethereal Grade II*-listed Church Cemetery.

A few days later a radio programme spoke to a listener in Hull, discussing the daily lockdown walks she had taken around the city’s General Cemetery, and how the stories written on its headstones had helped fulfil, to some extent, her need for social contact.

Then, a sketch of Edinburgh’s Warriston Cemetery appeared on my Instagram feed, its Tudor-arched central vaults just visible through a tangle of ivy-covered trees. Across Britain, it seemed, people had been rediscovering the country’s Victorian graveyards during the Covid pandemic.

You might also like best spring gardens to visit around the UK

This might sound incongruous at a time when we were facing death so profoundly, but author and taphophile (lover of graves) Peter Ross argues in his book, A Tomb With A View, that as well as being beautiful green spaces, where we can exercise away from overcrowded urban parks, they’ve also always been sources of comfort.

‘The people who lie in those graveyards have been through personal and economic depressions before, so we feel a neighbourly arm around us as we walk within them,’ he says.

Tombstone tourism is nothing new. For 200 years visitors to Rome have paid their respects at the graves of Keats and Shelley in the city’s Protestant Cemetery while travellers have long diverted to the Somme war graves on their way to ferries at Calais or Boulogne.

The stories within these spaces draw us to them, with celebrity a particular lure for some; Paris’s iconic Père Lachaise Cemetery only succeeded after the remains of Molière and the 12th-century lovers Abelard and Héloïse were transferred there.

You might also like No Mow May 2022: the best excuse for not mowing the lawn

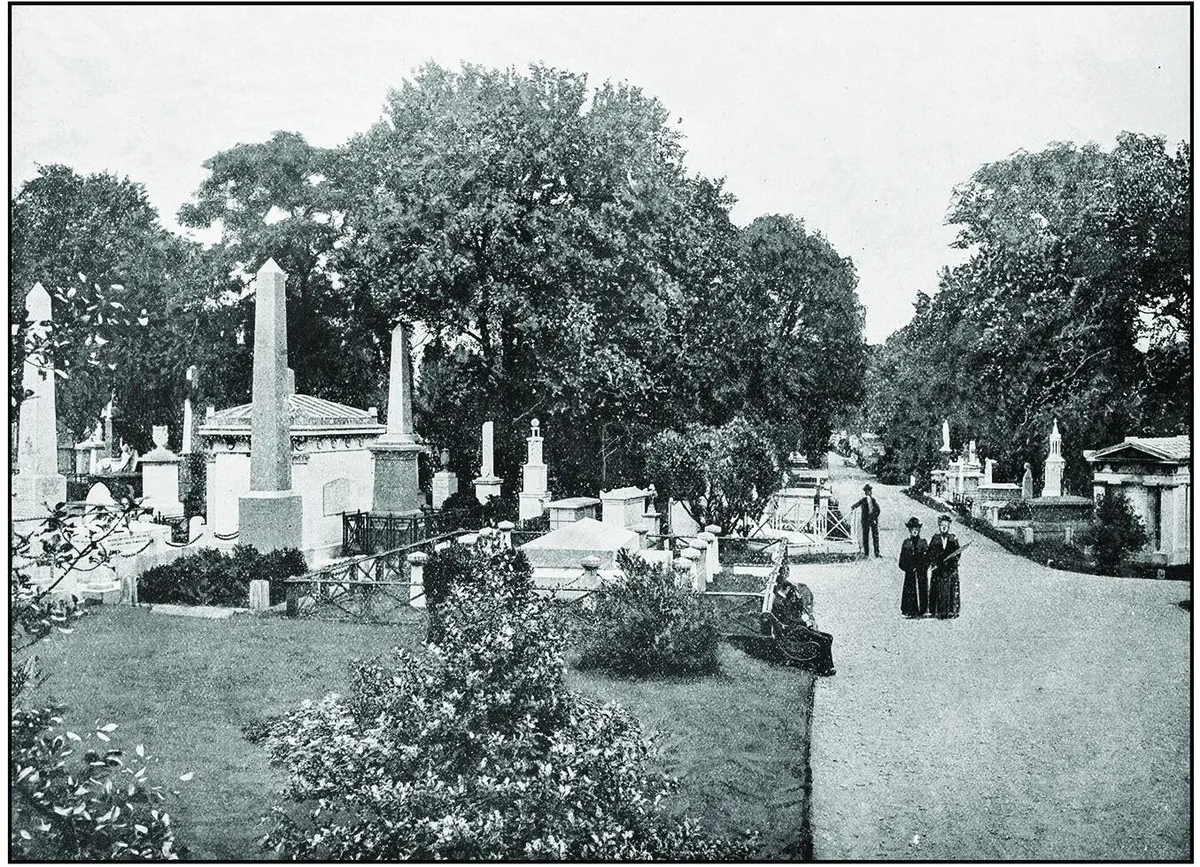

Just as significant, however, is the fact that many cemeteries were designed as visitor attractions from the outset. In the 1860s, Queen Victoria went for a carriage ride around Brompton Cemetery. While in 1859, Jules Verne visited Warriston Cemetery during a trip to Edinburgh, where he found the tombs were ‘like charming cottages where life flows past, leisurely and pleasant’.

London’s Highgate and Kensal Green even employed their own private police forces to maintain order since the cemeteries were so busy on Sundays: reports from the time talk of people picnicking. These were the days before public parks, explains Ian Dungavell, chief executive of Friends of Highgate Cemetery Trust. Cemeteries weren’t full of graves in the 1830s and 40s.

‘They were large areas of open space with monuments dotted around. They would feel almost like a sculpture garden. Highgate Cemetery, for example, put ads in the paper saying, “we’ve got this fantastic Egyptian architecture and the best views of town for miles around and it’s a great place to visit on a Sunday to get away from the smog and the bustle in the city”.’

You might also like where to buy rustic garden antiques

This wasn’t simply an attempt to improve public wellbeing. It was also a marketing exercise. Britain’s garden cemeteries began in the provinces with the opening of the Rosary Cemetery in Norwich in 1819, expanded through the next decade with necropolises in Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Newcastle and, eventually, reached London where seven cemeteries (collectively they became known as ‘the magnificent seven’) were built.

These sites were built as a response to pressure on older burial grounds as the Industrial Revolution brought more people to metropolises (and cholera and typhoid took their toll), a growing demand for non-denominational burial places and, significantly, as investments.

With many cemeteries built and run by ‘joint stock’ companies, the more attractive investors could make them the more people would visit them, and pay for burials in them. Time and expense went into the cemeteries’ design. They were sources of civic pride with as many conventions about their layouts and planting as the Victorians had rules and rituals about death and mourning.

Many were designed in the ‘pleasure ground’ style before Scottish horticulturalist JC Loudon published On The Laying Out, Planting and Managing of Cemeteries in 1843. He recommended they were built along grid systems and that planting should focus on conical evergreens.

From the start, creating a pleasant landscape was fundamental, says Ian. When many British garden cemeteries documented that they were modelled on Père Lachaise, ‘what they really meant was they were going to be beautiful and tasteful’. The aspirations revealed by the cemeteries’ architecture – Classical, Egyptian Revival or, most popularly, Gothic – are reflected in the number of cemeteries that now hold listed status.

You might also like antiques experts share their favourite places to visit

Within them, mausoleums and memorials gave sculptors, architects and gardeners a place to showcase their work. It also gave the great and good somewhere to carve out their social standing in perpetuity. And – as G K Chesterton wrote of ‘paradise by way of Kensal Green’ in 1913 – a suitable staging post on the path to the next world.

One area of planning the creators of the great garden cemeteries overlooked, however, was their upkeep. When the cemeteries reached capacity their income streams dried up. At around the same time there was a shift in attitudes as religious fervour declined. The scale of loss during the First World War saw ostentatious individual commemoration fall out of favour and cremations rose in popularity.

As the cemeteries became increasingly neglected the companies operating them began failing. Some closed altogether and converted to parks. Others were left to nature; while many are now valued wildlife sites, these also need management – the 18 species of bats at Manchester’s Southern Cemetery, and Highgate’s rare orb spiders, may be welcome, but Japanese knotweed is not.

This need for long-term income means that tourism is welcomed in many cemeteries, from tours to weddings. As more of us rediscover the idea of these spaces as the Victorians did – as spiritually suffused sculpture parks – we need to tread a fine balance, according to Peter Ross.

‘What’s important is that cemeteries find a way to bring in money while, if they can, maintaining the right for people to be buried within them. If they just become venues for leisure then they lose what makes them emotionally resonant. Having people continue to be buried in them is what makes cemeteries continue to live.’