When Tim Bowen started work in a small auction room in west Wales 30 years ago, he admits he didn’t know much about antiques. When somebody brought in a dilapidated old chair and the auctioneer asked him to put a notice on it that read ‘handle with care’, Tim thought it was a joke because he was the new boy. But the chair sold for £1,000. It was a Welsh stick chair. ‘That was it, I had to find out more,’ recalls Tim, who worked at the auction house for three years before moving to Richard Bebb’s dealership for another 15.Tim met his wife, Betsan, when she walked into the shop one day and bought a chair. ‘I kept going back,’ she recalls. ‘Tim would deliver things in person. One thing led to another and now we’re married with three children and two dogs!’

The couple set up business together in 2003, dealing in Welsh country furniture and folk art. Since then, they’ve published over 30 catalogues filled with all things rustic – from Carmarthenshire coffors (cupboards) to Welsh dressers – and have amassed a wealth of specialist knowledge about Welsh stick chairs, as well as a huge archive of images. ‘There wasn’t a book on Welsh stick chairs, so we thought we would write one,’ says Tim, simply. Of course, they weren’t known as ‘stick chairs’ always – it’s a term that’s used in the antiques world. ‘You get similar chairs in Ireland,’ reveals Tim. ‘They’re known as Irish ‘hedge’ or ‘famine’ chairs, and there are similar ones from the West Country, too, which is only 12 miles across the Bristol Channel from Wales. Over time, you get to recognise the Welsh ones, which are mostly made in ash or elm.’ Antique furniture books often describe these chairs as ‘primitive’ or ‘unusual’.

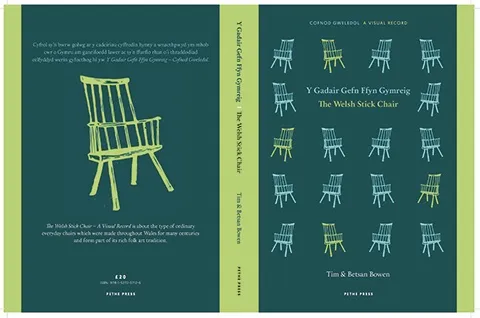

Tim and Betsan announce in the introduction of their new book, The Welsh Stick Chair: A Visual Record, that it is not a ‘definitive’ guide, because there are no records of who made these chairs or who owned them. ‘You can’t go to the library and look them up,’ Tim explains. ‘With silver, you can read the hallmark. With porcelain, you can look underneath it for marks. If you’re a dealer in fine mahogany, you can get a pattern book and findout exactly who designed it and when. But I just have to be honest and say: “I think this was made in Cardiganshire in the 18th century.” I don’t always know for sure,’ explains Tim.

Most stick chairs were made by craftsmen who worked in wood and had an understanding of it, rather than professional cabinetmakers.‘There is a great tradition of wood-working in west Wales,’ says Tim. ‘Cawl (soup) spoons, bowls, tables, gates – every community would have had a jobbing carpenter, somebody who knew how to find seasoned ash and could see the curve in a branch that would make the back of a chair. You can see similar methods of construction in a cottage roof scaled down in a chair.’

Most of the chairs Tim and Betsan see are 18th-century or early 19th-century but there are a few earlier 17th-century ones around, too. ‘It’s so difficult to date these pieces precisely,’ Tim acknowledges. ‘In the antiques world, specific dates are often revered, but country pieces aren’t like that.’The difference in value depends on patina. ‘I might buy a 19th-century chair because it has the best colour – it doesn’t matter that it’s not 18th-century,’ says Tim. ‘The contrast between the wood – for example, golden sycamore – and dark varnish is always beautiful.’A lot of chairs have been stripped of their original paint. ‘The ones that have survived intact and still have layers of old varnish – or even a blacksmith’s repair – always stand out to me,’ continues Tim. Restoration doesn’t devalue these pieces. In fact, it adds to their charm. ‘Although stick chairs were highly prized by their owners, they were meant to be sat on. They’re not works of art.’

The market for stick chairs is strong and getting stronger. ‘Some go to country cottages and some to modern city flats,’ says Betsan. ‘They’re sculptural pieces so look great in a contemporary setting as well as a more traditional one.’ Around 20 per cent of Tim Bowen Antiques’ customers live overseas, with lots of interest in America. ‘Country furniture and folk art is highly prized there, perhaps more so than here even,’ reveals Betsan. ‘There are also a lot of American woodworkers interested in making similar chairs today.’

Unsurprisingly, Tim and Betsan’s Ferryside home in Carmarthenshire is the epitome of cosy. Kitchen walls painted in Farrow & Ball’s bold Charlotte’s Locks orange provide a colourful backdrop for a beautiful Welsh dresser, antique salt box and spoon rack. ‘Our house isn’t much different from the shop really,’ laughs Betsan. ‘Success to us is managing to make a living, living somewhere we love to live and doing something we love to do.’