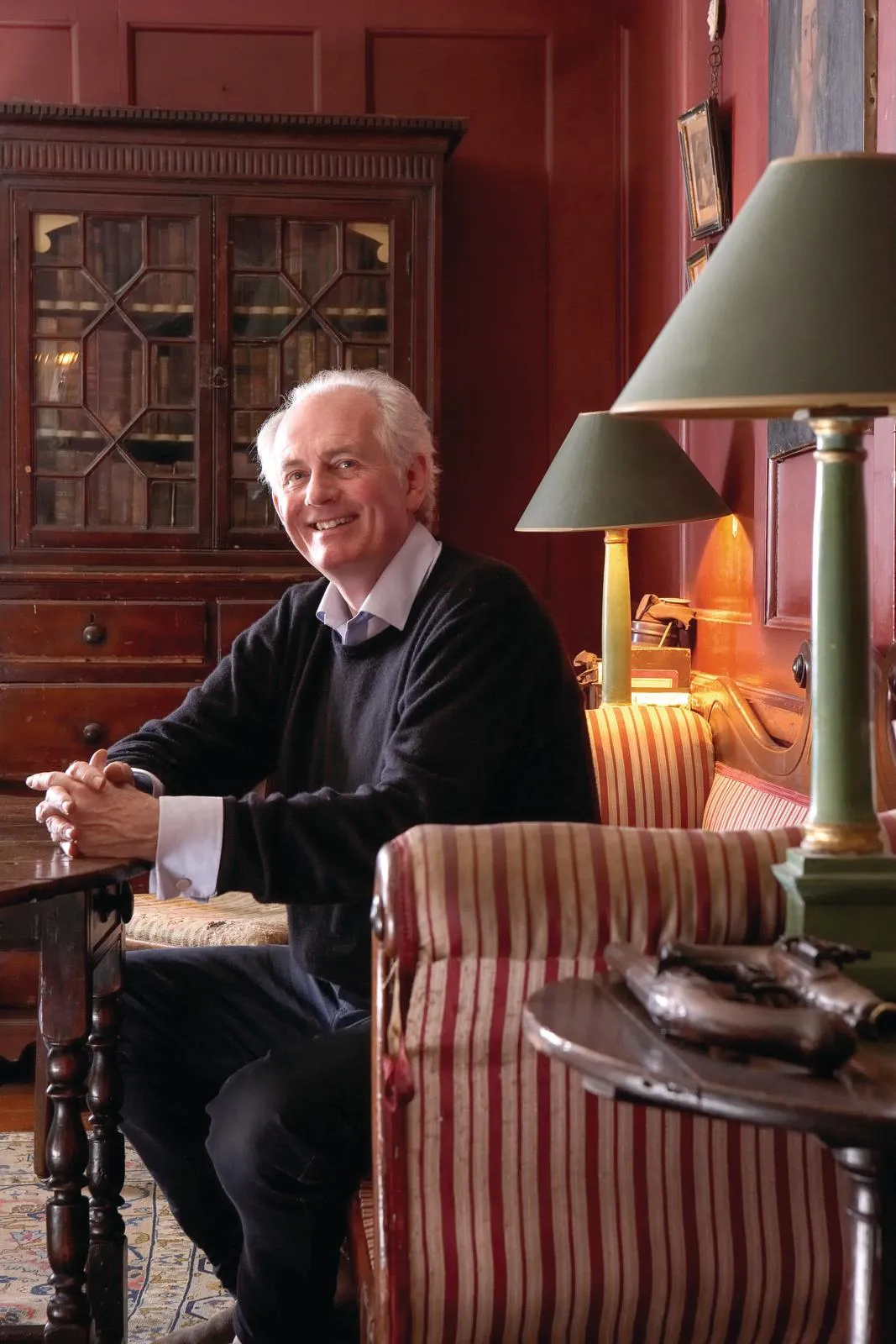

As a teenager I loved 18th-century buildings,’ says Dan Cruickshank, the television presenter and art historian. And he recalls being ‘dazzled’ by London’s Georgian terraces, ‘particularly those around Bloomsbury’. By his early twenties, however, his passion had taken him further east, to Spitalfields, which is where he lives now. His 18th-century townhouse is one of many in the area that he helped save from demolition in the Seventies.

Built in 1727 by Mr Bunce and Mr Brown, Dan’s house was part of Spitalfields’ rapid expansion following the arrival of thousands of Huguenot silk workers fleeing persecution in France. The first owners, John and James Payton, may or may not have been refugees, but they were certainly involved in the silk industry, most likely as merchants. ‘It’s possible they were French,’ says Dan. ‘They had money and taste, and gave themselves a good pedigree with all the design flourishes on the house.’

But Mr Bunce and Mr Brown also had a hand in all these elegant architectural details. They would have taken inspiration from the new buildings going up around the city, says Dan, sketching anything that intrigued them. ‘Pattern books didn’t come along until later,’ he explains, clearly impressed by the way speculative builders ‘embraced the big ideas of the Classical age: the architectural language of Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren.’

By the time Dan first came to know the area in the late 1960s, drawn by Hawksmoor’s famous Christ Church and the range and quality of the surrounding architecture, Spitalfields was a virtual slum; entire terraces sat silent and empty. ‘It was all listed, but no one really cared. Much of the area was dilapidated.’

You might also like inside a colourful Georgian townhouse

Although the houses hadn’t been properly maintained, they also hadn’t been subjected to ‘intrusive home improvements’. Original details remained intact because neither landlords nor tenants could afford to replace them. ‘You could almost say these buildings were protected by poverty,’ he says.

By the time Dan moved into his house in the late-1970s, it had been empty for close to 20 years, yet he knew it intimately. ‘I’d visited it many times before it came onto the market,’ he says. ‘It was all boarded up at the front, but at the back it was derelict, so I used to climb in through the window.’

What he found inside was eerily beautiful. ‘It was a magical experience wandering around this very early-18th-century house, with its dentil cornicing and the original dresser in the basement.’ Remarkably, it was still fully furnished. ‘It was all very odd,’ says Dan. ‘Filled with late-Victorian and Thirties furniture, all rotting in situ.’

When the opportunity to buy the house arose, he jumped at the chance, despite extensive water damage and collapsed ceilings. Fortunately, the floors remained solid and the panelling was largely unaffected. ‘I moved in straightaway, living in the driest parts,’ he says. With its outside loo, cold water and gas lights, Dan has fond memories of those first years, living in ‘strange and romantic circumstances’.

You might also like a striking flat in a Georgian townhouse

The restoration was a slow and painstaking process, but filled with fascinating discoveries. In the green dining room, panelling in the alcove suggested that it had once housed a built-in shelf or cabinet so he constructed a replacement using timber salvaged from other houses in the area. ‘It’s my monument to lost East End London,’ he says.

When it came to furnishing the house he sought out pieces from the late-17th and early-18th centuries. ‘It’s all of the culture of the house. Most of it was very cheap and came from local markets. It all has a humdrum quality, which I like.’

Looking around the house today, it’s clear the renovation has been a real labour of love and Dan has shown a similarly dogged approach to researching its history. He knows the names and professions of everyone who has lived in his home and can even point to details particular to certain families.

Dan believes that little holes to the side of all the internal doorways were made by a Jewish family who were tenants for a while. ‘It’s where they would have hung their mezuzahs. There were only two Jewish families on the street and both their houses bear the same marks.’ Dan has also learned that the last family to live in the house was paid to leave by the landlord. ‘This was common practice in the Forties and Fifties and this is why they abandoned furniture.’

Dan has lived in his house longer than any of its previous occupants, but he revels in the sense of their presence and, despite keeping the house as unchanged as possible, he’s confident that he has left his stamp, too. ‘If the house is going to be haunted by anyone,’ he laughs, ‘it’ll be me.’